this upset. So I went ahead and told

him."

![]() The chaplain wrote something on a

piece of paper, put it in an envelope, and said,

"Take this over to Personnel."

The chaplain wrote something on a

piece of paper, put it in an envelope, and said,

"Take this over to Personnel."

![]() "I said 'Okay," and I kind

of trudge into the personnel section and hand it to the

guy behind the counter.

"I said 'Okay," and I kind

of trudge into the personnel section and hand it to the

guy behind the counter.

![]() "He goes out of sight and comes

back with what they call a '201 file,' a great big brown

file that had on it the name: 'Anderson -- Rejected.'

"He goes out of sight and comes

back with what they call a '201 file,' a great big brown

file that had on it the name: 'Anderson -- Rejected.'

![]() "He took a crayon or something

and lined out the word 'Rejected' and stamped on there,

'Accepted.'

"He took a crayon or something

and lined out the word 'Rejected' and stamped on there,

'Accepted.'

![]() "I was in!"

"I was in!"

![]() Two days later, Anderson -when asked

if he wanted to -- volunteered for the Army Air Corps.

Two days later, Anderson -when asked

if he wanted to -- volunteered for the Army Air Corps.

![]() "So I was discharged from the

Army after two days and re-enlisted in the Army Air

Corps, [which later] became the Air Force."

"So I was discharged from the

Army after two days and re-enlisted in the Army Air

Corps, [which later] became the Air Force."

![]() By then it was March of 1946.

Anderson would serve the next 20 years in the Air Force,

working usually as either a chaplain's assistant or a

personnel clerk. He was twice given the commendation

medal twice for his work in personnel administration.

By then it was March of 1946.

Anderson would serve the next 20 years in the Air Force,

working usually as either a chaplain's assistant or a

personnel clerk. He was twice given the commendation

medal twice for his work in personnel administration.

![]() If gratitude to the nuns who taught

him love helped make Anderson a life-long Catholic,

gratitude to the Air Force helped make him a career man.

If gratitude to the nuns who taught

him love helped make Anderson a life-long Catholic,

gratitude to the Air Force helped make him a career man.

![]() That problem eye and the Dumbo ears

were, again, what started it.

That problem eye and the Dumbo ears

were, again, what started it.

![]() At the time, between 1947 and 1949,

Anderson was in Hawaii, in his first overseas assignment.

Because of headaches, he'd gone in to see an Air Force

doctor, a "Dr. King."

At the time, between 1947 and 1949,

Anderson was in Hawaii, in his first overseas assignment.

Because of headaches, he'd gone in to see an Air Force

doctor, a "Dr. King."

![]() "I was just joking around about

my eye, and I kept looking down, and it kind of disturbed

him that I wouldn't look him straight in the eye.

"I was just joking around about

my eye, and I kept looking down, and it kind of disturbed

him that I wouldn't look him straight in the eye.

![]() "Well, I was self-conscious; I

didn't like people staring at my crossed-eye. So [Dr.

King] made arrangements to operate on my left eye.

"Well, I was self-conscious; I

didn't like people staring at my crossed-eye. So [Dr.

King] made arrangements to operate on my left eye.

![]() "He said, 'I can't help your

vision, but you won't be so self-conscious about it.' So

he did pull the muscle over and straightened the eye out.

"He said, 'I can't help your

vision, but you won't be so self-conscious about it.' So

he did pull the muscle over and straightened the eye out.

![]() "So I was joking and said,

'Gee, how about my ears, ya know?'

"So I was joking and said,

'Gee, how about my ears, ya know?'

![]() "Sure enough," says

Anderson, "he made arrangements with a plastic

surgeon and had the ears pinned back.

"Sure enough," says

Anderson, "he made arrangements with a plastic

surgeon and had the ears pinned back.

![]() "So out of gratitude, more than

anything else, I stayed in the military for 20 years --

just to pay them back, for being so good to me. Because

being an orphan and ... with a grandmother who was a

widow, I'd never have been able to afford it."

"So out of gratitude, more than

anything else, I stayed in the military for 20 years --

just to pay them back, for being so good to me. Because

being an orphan and ... with a grandmother who was a

widow, I'd never have been able to afford it."

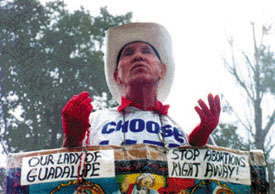

![]() The final chapter in creating the

Pro-Life Andy Anderson people in Reno know today -- sort

of a rapid-fire-versifying, cowboy-hatted version of an

Old Testament prophet -- began in 1964.

The final chapter in creating the

Pro-Life Andy Anderson people in Reno know today -- sort

of a rapid-fire-versifying, cowboy-hatted version of an

Old Testament prophet -- began in 1964.

![]() That was when Anderson married a

Boston widow with a 9-year-old son. It was two years

before Anderson was to complete his 20-year Air Force

career.

That was when Anderson married a

Boston widow with a 9-year-old son. It was two years

before Anderson was to complete his 20-year Air Force

career.

![]() "In the service I had joined a

Catholic correspondence club and met a Catholic girl by

mail," he says. "When I was stationed in North

Dakota and she lived in Massachusetts, we sent pictures

to each other and everything."

"In the service I had joined a

Catholic correspondence club and met a Catholic girl by

mail," he says. "When I was stationed in North

Dakota and she lived in Massachusetts, we sent pictures

to each other and everything."

![]() Anderson eventually took a furlough

to go meet her and her family, and, he says, ultimately

fell in love.

Anderson eventually took a furlough

to go meet her and her family, and, he says, ultimately

fell in love.

![]() It was in 1969 that the new family

moved to Reno. However, just six years later, in 1975,

Anderson's wife had a stroke.

It was in 1969 that the new family

moved to Reno. However, just six years later, in 1975,

Anderson's wife had a stroke.

![]() Suddenly she was unable to walk or

talk. For the next eight and a half years, until her

death in 1984, Anderson would take care of his helpless

wife.

Suddenly she was unable to walk or

talk. For the next eight and a half years, until her

death in 1984, Anderson would take care of his helpless

wife.

![]() But 1975 was a watershed year in two

other respects also. It was the year Anderson learned

about the new reality in America -- and Reno -- of

abortions. It was also the year the entire subject became

personal.

But 1975 was a watershed year in two

other respects also. It was the year Anderson learned

about the new reality in America -- and Reno -- of

abortions. It was also the year the entire subject became

personal.

![]() "I was reading the paper,"

says Pro-Life, "and it said something about some

people were having a protest in front of a local abortion

mill. And I said, 'Well, what do they mean by

that?'"

"I was reading the paper,"

says Pro-Life, "and it said something about some

people were having a protest in front of a local abortion

mill. And I said, 'Well, what do they mean by

that?'"

![]() At the time, he says, the word

'abortion' meant the same to him as a miscarriage.

At the time, he says, the word

'abortion' meant the same to him as a miscarriage.

![]() When he was told, "Oh, that's

where they kill babies," he didn't believe it.

When he was told, "Oh, that's

where they kill babies," he didn't believe it.

![]() "I couldn't comprehend

it," says Anderson. "So I went down to the

abortion mill on Mill Street -- when it was located there

-- and about 20-22 people were marching up and down in

front.

"I couldn't comprehend

it," says Anderson. "So I went down to the

abortion mill on Mill Street -- when it was located there

-- and about 20-22 people were marching up and down in

front.

![]() "So I figured, well, if they're

killing babies in that building, I'll join these people.

Well, I just got in this little formation and walking up

and down with one of these signs, and some guy came up

and handed me a brochure and it says 'Life or Death.' And

it showed pictures of babies who were actually killed by

an abortion -- by insulin, by curettage, by GNC. And I

said, 'My God, those are real babies. That's not a blob

of tissue. You could see heads and legs.'

"So I figured, well, if they're

killing babies in that building, I'll join these people.

Well, I just got in this little formation and walking up

and down with one of these signs, and some guy came up

and handed me a brochure and it says 'Life or Death.' And

it showed pictures of babies who were actually killed by

an abortion -- by insulin, by curettage, by GNC. And I

said, 'My God, those are real babies. That's not a blob

of tissue. You could see heads and legs.'

![]() "So when I saw these pictures,

it hit me like a sledgehammer and I knew what abortion

really was. I just rebelled against it naturally.

"So when I saw these pictures,

it hit me like a sledgehammer and I knew what abortion

really was. I just rebelled against it naturally.

![]() "Because that could have been

me, if they'd had it legal back when my father deserted

my mother. So, just as I objected to that birth control

woman, Margaret Sanger, just on the principle of

preventing my conception in the first place, it was even

more horrible to me to think of killing babies after

they'd already been conceived."

"Because that could have been

me, if they'd had it legal back when my father deserted

my mother. So, just as I objected to that birth control

woman, Margaret Sanger, just on the principle of

preventing my conception in the first place, it was even

more horrible to me to think of killing babies after

they'd already been conceived."

![]() Relatively speaking, however,

Anderson says he was still "more or less

objective" on the issue.

Relatively speaking, however,

Anderson says he was still "more or less

objective" on the issue.

![]() "I wasn't too active. I was

taking care of my wife."

"I wasn't too active. I was

taking care of my wife."

![]() That was soon to change.

That was soon to change.

![]() "And then my stepson had gotten

involved with a girl, and he came to me one day and

wanted to borrow the money to get an abortion for his

girl friend.

"And then my stepson had gotten

involved with a girl, and he came to me one day and

wanted to borrow the money to get an abortion for his

girl friend.

![]() "It was like he hit me in the

face with a sledge hammer. I said, 'What do you mean,

give you money for an abortion? I'm not going to give you

any money to kill a baby. And I didn't order him out of

the house, I just said, 'I can't face you with something

like that.'

"It was like he hit me in the

face with a sledge hammer. I said, 'What do you mean,

give you money for an abortion? I'm not going to give you

any money to kill a baby. And I didn't order him out of

the house, I just said, 'I can't face you with something

like that.'

![]() "What made me feel even more

guilty was, I had given him a truck and a chainsaw to

learn to be independent and cut firewood so he could

learn to take care of himself.

"What made me feel even more

guilty was, I had given him a truck and a chainsaw to

learn to be independent and cut firewood so he could

learn to take care of himself.

![]() "And he used that as the

collateral to borrow the money to get the abortion for

his girl friend."

"And he used that as the

collateral to borrow the money to get the abortion for

his girl friend."

![]() Pro-Life Andy Anderson is choking

up, eyes starting to glisten, in his distress.

Pro-Life Andy Anderson is choking

up, eyes starting to glisten, in his distress.

![]() "What happened was that he had

given ...

"What happened was that he had

given ...

![]() "What happened was ... one of

his girl friend's girl friends had driven her over to

Oakland, California to the abortion mill there...

"What happened was ... one of

his girl friend's girl friends had driven her over to

Oakland, California to the abortion mill there...

![]() "I got the phone number of the

abortion mill she was in [and] got hold of her on the

telephone -- I won't use her real name -- let's say..

"I got the phone number of the

abortion mill she was in [and] got hold of her on the

telephone -- I won't use her real name -- let's say..

![]() "Betty, please.. I'll adopt the

baby, I'll give you and my son a free home... Anything.

Just get out of there, please.

"Betty, please.. I'll adopt the

baby, I'll give you and my son a free home... Anything.

Just get out of there, please.

![]() "At the time, my wife was in

the bedroom with her stroke. I had an extension on my

phone, so I was in the kitchen. I got on my knees in the

kitchen, and said 'Dear God, please, don't let me be too

late.

"At the time, my wife was in

the bedroom with her stroke. I had an extension on my

phone, so I was in the kitchen. I got on my knees in the

kitchen, and said 'Dear God, please, don't let me be too

late.

![]() "Anyway, she couldn't even talk

straight. They had her so doped up. She said "Iii

donnn't knowww. They gave me something and I can hardly

stand up...

"Anyway, she couldn't even talk

straight. They had her so doped up. She said "Iii

donnn't knowww. They gave me something and I can hardly

stand up...

![]() "I said, 'I don't care, call a

cab, get out of there. I made arrangements for you at a

hospital over in San Francisco.. and just go over there

and tell the pastor I'm going to take care of you until

everything is accomplished.

"I said, 'I don't care, call a

cab, get out of there. I made arrangements for you at a

hospital over in San Francisco.. and just go over there

and tell the pastor I'm going to take care of you until

everything is accomplished.

![]() "She said, 'Iii donnn't knowww.

I think it's too late' or something and she hung up.

"She said, 'Iii donnn't knowww.

I think it's too late' or something and she hung up.

![]() "She went through with the

abortion, and I can't prove it was suicide, but not too

long afterwards, she killed herself in a single car

accident out on the highway. Only 20 years old, in 1979.

"She went through with the

abortion, and I can't prove it was suicide, but not too

long afterwards, she killed herself in a single car

accident out on the highway. Only 20 years old, in 1979.

![]() "Not only did I lose a future

grandchild, but I lost a future daughter-in-law.

"Not only did I lose a future

grandchild, but I lost a future daughter-in-law.

![]() "I said, 'Dear God, what can I

do." I felt like I was a failure in my own family. I

couldn't even protect my own unborn grandchild. What can

I do to help others?

"I said, 'Dear God, what can I

do." I felt like I was a failure in my own family. I

couldn't even protect my own unborn grandchild. What can

I do to help others?

![]() "So I said, 'Dear God, use me

-- any way you see fit. I don't care, I'll crawl on my

knees through the middle of town.

"So I said, 'Dear God, use me

-- any way you see fit. I don't care, I'll crawl on my

knees through the middle of town.

![]() "It was just a sort of

expression," says Anderson, laughing. But it soon

seemed that was exactly what God wanted.

"It was just a sort of

expression," says Anderson, laughing. But it soon

seemed that was exactly what God wanted.

![]() "So I put a notice in the

paper, in January, on the anniversary of the Roe v. Wade

decision, that Andy Anderson is going to crawl on his

knees from the Pioneer Theater down Mills Street, past

the local abortion mill, all the way to Washoe Med, as an

act of atonement asking God to have mercy on our country

and to beg people to stop killing their babies ...

"So I put a notice in the

paper, in January, on the anniversary of the Roe v. Wade

decision, that Andy Anderson is going to crawl on his

knees from the Pioneer Theater down Mills Street, past

the local abortion mill, all the way to Washoe Med, as an

act of atonement asking God to have mercy on our country

and to beg people to stop killing their babies ...

![]() "So.. I did .. and [laughing]

it was winter-time, and there's still ice and snow on the

sidewalk ... and I don't know what I'd got myself into,

and if I'd known ahead of time, I probably would have

chickened out, you might say. So I went ahead and I

crawled on my knees all the way.

"So.. I did .. and [laughing]

it was winter-time, and there's still ice and snow on the

sidewalk ... and I don't know what I'd got myself into,

and if I'd known ahead of time, I probably would have

chickened out, you might say. So I went ahead and I

crawled on my knees all the way.

![]() "I was carrying an

anti-abortion sign which I could use as a sort of a

support, so I wouldn't fall down flat on my face...and as

soon as I got there I just collapsed.

"I was carrying an

anti-abortion sign which I could use as a sort of a

support, so I wouldn't fall down flat on my face...and as

soon as I got there I just collapsed.

![]() "My knees were sore for a month

after that. I still have scars, because I did it again,

about three years later."

"My knees were sore for a month

after that. I still have scars, because I did it again,

about three years later."

![]() Rolling up his pant leg, he points

to his knee and shows where the skin broke open.

Rolling up his pant leg, he points

to his knee and shows where the skin broke open.

![]() "But it made people stop. And I

said, 'If only one life is saved, it's worth it."

Personally, Anderson also felt it might help atone for

the loss of his own unborn grandchild.

"But it made people stop. And I

said, 'If only one life is saved, it's worth it."

Personally, Anderson also felt it might help atone for

the loss of his own unborn grandchild.

![]() So that was when Anderson began to

develop what he now calls his 'persona.' -- the panoply

of black and red costumery, crucified baby dolls, signs

covered with anti-abortion doggerel, old cars with nearly

every square inch covered with bumper stickers, garish

ads in the newspapers and Calvary-flavored media events,

that Reno has come to know over the last 20 years.

So that was when Anderson began to

develop what he now calls his 'persona.' -- the panoply

of black and red costumery, crucified baby dolls, signs

covered with anti-abortion doggerel, old cars with nearly

every square inch covered with bumper stickers, garish

ads in the newspapers and Calvary-flavored media events,

that Reno has come to know over the last 20 years.

![]() Today Pro-Life Anderson is 69 years

old, and -- knowing his life could come to an end at any

moment -- is trying to get his affairs in order.

Today Pro-Life Anderson is 69 years

old, and -- knowing his life could come to an end at any

moment -- is trying to get his affairs in order.

![]() Because his older brother died a

year ago January, from lung cancer, Pro-Life knows that

he could follow at any time. He is making arrangements so

that, when that happens, he will buried back in Georgia,

next to his brother and his mother.

Because his older brother died a

year ago January, from lung cancer, Pro-Life knows that

he could follow at any time. He is making arrangements so

that, when that happens, he will buried back in Georgia,

next to his brother and his mother.

![]() That is the mother who died about 65

years ago, when Anderson was just three. Of her, he has

only one memory. It is archetypal.

That is the mother who died about 65

years ago, when Anderson was just three. Of her, he has

only one memory. It is archetypal.

![]() "I was in a nursery, and

remember this old model T Ford, with my grandfather

behind the wheel...

"I was in a nursery, and

remember this old model T Ford, with my grandfather

behind the wheel...

![]() "And I can just remember coming

out of the building...

"And I can just remember coming

out of the building...

![]() ... and going down the sidewalk, and

my mother's arms are open like that.." -- he

demonstrates --

... and going down the sidewalk, and

my mother's arms are open like that.." -- he

demonstrates --

![]() "..and I'm just going to my

mother's arms,

"..and I'm just going to my

mother's arms,

![]() ...and they're open..."

...and they're open..."